Over the years I’ve missed seeing an aurora several times, but on the evening of Thursday 27th February 2014, I spotted an aurora for the first time and from virtually my own doorstep.

Way back in the 90’s, I was in Calgary, Canada, at an early conference about the Square Kilometre Array. At breakfast one day, the partner of a colleague who’d driven overnight through the Rockies to meet us said she’d seen a great aurora. I stayed up most of the next night…nothing.

Last solar maximum, about 12 years ago, Tom Muxlow arrived in the Jodrell Bank tearoom one morning regaling us with tales of how there’d been an aurora visible the night before. To see one so far south is very unusual and, of course, it didn’t appear again.

Last year, my wife and I went to Iceland for a holiday. Spectacular place and a great break. Of course we had hopes of seeing an aurora but sadly it was cloudy throughout most of our stay, but on those nights when there were gaps overhead, no aurora.

So, when last Thursday evening, stories of the aurora being visible from quite far south in the UK began to appear on Twitter, it was time to kick off the slippers, wrap up warm, grab the camera and head for the hills!

We live in Manchester , so light pollution would have killed any chance of seeing the aurora from home. What’s needed is a dark sky and a clear northern horizon. We headed east out of Manchester, along the M67 and onto the Woodhead Pass through the Pennine hills towards Sheffield. Part way along the pass, a left turn on to the A6024 towards Holmfirth took us up onto the top of the Pennines where there is a transmitter station at Holme Moss.

I figured this would be a good spot from where to look out for the Northern Lights as there’s less light pollution to the north as this handy map shows. But, as it happens, it’s also a location with historical importance to Jodrell Bank.

In the 1950’s and 60’s astronomers at Jodrell Bank (including Hanbury Brown, Jennison, Das Gupta and Palmer) were investigating the angular size of radio sources – a project which helped lead to the identification of quasars. In order to increase the resolution of their observations they developed the technique of radio-linked interferometry, bringing signals from ever more distant radio antennas back to Jodrell for combination with various home antennas (including the 218-ft transit telescope and then the 250-ft Mark I, now the Lovell Telescope).

Eventually they moved their remote antenna to the far side of the Pennines with no direct line of sight back to Jodrell Bank. They needed a repeater station on the hills and so they borrowed the BBC transmitter site at Holme Moss (Elgaroy, Morris & Rowson, 1962).

Unfortunately, when we arrived at the Holme Moss transmitter station we realised that floodlights on the building at its base destroyed our dark adaptation. We drove on a little further down the far side of the hill. But from here the towns down below were visible, as was their light pollution. We parked up briefly and I took a couple of test photographs. No aurora could be seen by eye and I didn’t immediately see anything on the back of the camera so we decided to turn round and head back past the transmitter station, putting the hill between us and the direct light pollution. As it happens, when looking at the photos later, the green of the aurora is just visible through the light pollution, as is one of the red pillars above it.

From the second spot the transmitter station was above us, next to a dip in the hills. I started taking long exposure photos but these only showed thin cloud cover photos lit by the glow of streetlights below. However, after 15 minutes or so the skies began to clear and the green glow of the aurora appeared! At last!

Most obvious in the dip in the hills to the north and visible to the unaided eye, but not bright, the green colour was very apparent on photos. Also appearing in photos, but not visible to the eye alone, was the red glow above it. The photos also show structure in the green aurora.

The glow of the aurora comes from charged particles flooding down the Earth’s magnetic field (in this case, triggered by a solar coronal mass ejection two days earlier which caught the Earth a glancing blow) and colliding with atoms and molecules in the atmosphere. The collisions energise the atmospheric atoms which then relax back to their lower energy states, emitting photons with specific energies corresponding to the colours we see.

The green glow is from oxygen atoms 60 or more miles above the Earth’s surface. But what causes the red glow which very clearly sits above the green? It turns out that this is another energy transition in oxygen with a different energy gap and hence a different color of light is produced when it relaxes back.

As explained in this aurora FAQ, in the green transition, the oxygen atom sits at the upper energy level typically for 3/4 second before falling back and emitting a photon. Whereas in the red transition, the delay is far longer, about two minutes. The extra time for the red transition increases the chance that the energised atom will collide with another particle and so be de-energised without emitting a photon. At high altitudes where the density of atoms is low, there is a far greater chance that the energised atoms will last long enough to emit the red glow, explaining why the red is seen above the green. At the lowest altitudes, even the green transitions are de-energised by collisions and all that is left is a purple colour caused by emission from nitrogen molecules. [You may also like this blog post about aurorae by Jim Wild of Lancaster University.]

As the aurora waxed and waned over the next hour or so, I amused myself with some photos to the west showing Jupiter, Orion and Sirius above the glow of the lights of Manchester.

Up on the hills there was no mobile phone signal but when we returned to Manchester, there was a voicemail message from the BBC inviting me on to the Breakfast TV programme the next morning to discuss the aurora and the amazing photos that viewers had sent in from around the country.

Not only did I get to see the aurora for the first time I also got a new job title – astronomist!

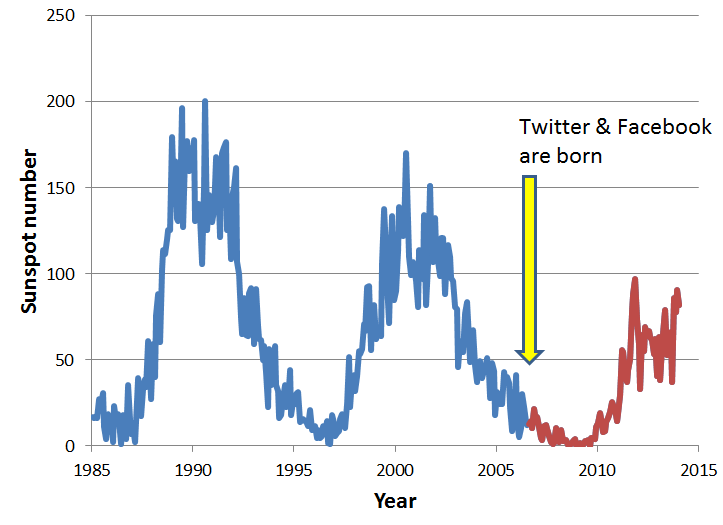

Clearly lots of people had gone out that Thursday evening to spot the aurora and take photos. Thinking back to my previous experiences of hearing about aurorae the day after and so missing my opportunity, this time I’d been alerted by Twitter. It struck me that this was the first solar maximum since the advent of social media and it was this that had enabled so many to get a glimpse of one of the world’s great natural phenomena.

One response to “Aurora spotting near Manchester”

[…] buntes, ein buntes irisches, ein britisches von 51°N und ein ein All-Sky aus den Niederlanden, ein Bericht aus Manchester sowie weitere Artikel hier, hier, hier (Bilder) und […]